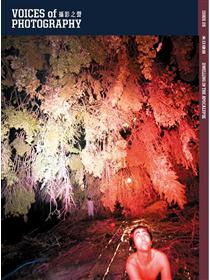

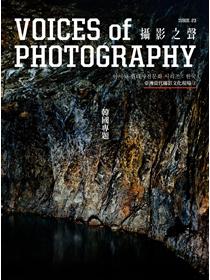

「亞洲當代攝影文化現場系列」是我們聚焦亞洲各地影像文化與創作實踐 的系列計畫,嘗試透過亞際跨域連結與在地論述視野,拓展我們對於攝影 在亞洲的實踐歷程、視覺經驗、文化及其論域的認識座標,並藉此作為影 像歷史與認識論的持續省思。 「沖繩專題」是此系列的第二輯,特別邀請影像研究者暨策展人町田惠美 與許芳慈共同擔任客座主編。

本期採雙向閱讀編輯,集結文論與訪談,穿 越沖繩糾結的被殖民史與帝國陰霾,在霸權的支配和抵抗的鬥爭之間,批 判地觀看沖繩的影像,以及作為影像的沖繩。 幾世紀前,位於太平洋上的琉球列島尚未成為「沖繩」,而是存在著一個 封建君主制的國度——琉球王國,後經日本薩摩藩的島津氏入侵與大日本 帝國擴張,廢琉設藩遭到併吞殖民,於1879年以「沖繩縣」編入日本國家 體系之內。在二戰的尾聲、1945年激烈的沖繩島戰役後,美國的佔領統治 期長達二十七年,沖繩從此劃進冷戰年代的軍事戰略島鏈。即使至1972年 美國將沖繩「返還」日本,在「日美同盟」的交換條件下,僅為日本本土 面積千分之六的沖繩,卻佈建了整體駐日美軍逾七成的軍事設施與基地。 對某部分的沖繩來說,「戰後」彷彿被無限延長,使這個亞熱帶之島,彌 漫著由地緣政治與新帝國主義擊燃而仍未散去的煙硝。

本專題介紹國吉和夫、石川真生、比嘉豐光與石川龍一等沖繩的影像實踐 者,追索他們的生命經驗與攝影的多重構成,以及其間複雜的政治性問題 意識;同時透過評論者仲里效、岡本由希子、仲宗根香織與井上間從文的 專文,將影像之於沖繩、之於歷史,由慣常對於「如何再現」的注意力, 置放於「如何建構」的維度。從而提示了影像不僅僅是從殖民的情境中派 生,同時也反饋到殖民的情境裡,需要加以細緻地解析。 在專題的製作期間,由全球疫情激化的國際角力波濤洶湧。與沖繩同列第 一島鏈的台灣等地讀者,閱讀本專題,或許會因類似的歷史背景與政治局 勢處境而更能與沖繩共感。而在沖繩所帶來的種種啟示中,我們也將意識 到對於當下的世界正在發生的反抗——無論是以國家主義修辭掩飾的極權 主義和種族主義,或是以經濟復甦為號召的資本主義巨靈回魂,除非我們 投入更多行動與關注,否則任何國家的「強國夢」,都會是人類史上的惡 夢一場。

The “A Study of Contemporary Photography in Asia” series is a serial project that focuses on imagery culture and creative practice in various regions of Asia. Through this connection and a view that pans across Asia, we are trying to expand our understanding of the process of practice, visual experience, culture and the identifying coordinates of photography in Asia, and using such knowledge as a continuous reflection of imagery history and epistemology. Second in the series is the Okinawa issue that features Machida Megumi and Hsu Fang-Tze, both imagery researchers and curators, as our guest editors. This issue adopts a dual reading and editing process; a combination of essays and interviews brings readers through the complicated colonial history and the burden of empiricism on the island, taking a critical view of Okinawa’s imagery, and Okinawa as an imagined object while it struggled against hegemony. Several centuries ago, there existed no “Okinawa”, but the Ryukyu Kingdom, a feudal kingdom in the Ryukyu Islands in the Pacific Ocean. After the invasion by the forces of the feudal domain of Satsuma, and subsequently by the Empire of Japan, the Ryukyu Islands were annexed and colonized, and in 1879, established as the Okinawa Prefecture. At the end of the Second World War in 1945, the U.S. forces occupied and ruled Okinawa for 27 years, sealing its fate in the strategic chain of islands in the Cold War era. Even when the U.S. forces “returned” Okinawa to Japan in 1972, the island, which only constitutes 0.6% of Japan’s total land area, houses more than 70% of the U.S.s military facilities and bases stationed in the whole country under the US-Japan Security Alliance. To some parts of Okinawa, it almost feels like that the “post-war” era never ended, surrounding this subtropical island with a plume of smoke that rose from the collision between geopolitics and new imperialism. In this series, we take a look at the layered composition of the life experiences and photography by Okinawan imagery practitioners Kuniyoshi Kazuo, Ishikawa Mao, Higa Toyomitsu and Ishikawa Ryuichi, as well as the complicated political consciousness that is birthed from this interaction. We also move our focus from the question of “how to represent” to “how to construct” the background of Okinawa and its history through the essays by Nakazato Isao, Okamoto Yukiko, Nakasone Kaori and Inoue Mayumo. Through such a redirection of focus, we see the need for a careful analysis as it shows us that imagery is not only generated from colonization, but also feeds back into the issue. While putting this issue together, the world is being ravaged by the COVID-19 pandemic, intensifying power rivalries. We imagine that our readers in Taiwan and other areas, which belong in the first island chain alongside Okinawa, would feel even more relevance to the island (Okinawa), given our similar histories and political situations. As we feel inspired by Okinawa in many ways, we also become aware of the 1 struggles that are happening around the world, whether it is one against totalitarianism and racism under the mask of nationalistic rhetoric, or the return of capitalism in the name of economic recovery. Until we put into action our words and resist, any dream of a “nation of great power” is but a nightmare for the history of humankind.

1收藏

1收藏

優惠價: 9 折, NT$ 405 NT$ 450

本商品已絕版

「亞洲當代攝影文化現場系列」是我們聚焦亞洲各地影像文化與創作實踐 的系列計畫,嘗試透過亞際跨域連結與在地論述視野,拓展我們對於攝影 在亞洲的實踐歷程、視覺經驗、文化及其論域的認識座標,並藉此作為影 像歷史與認識論的持續省思。 「沖繩專題」是此系列的第二輯,特別邀請影像研究者暨策展人町田惠美 與許芳慈共同擔任客座主編。

本期採雙向閱讀編輯,集結文論與訪談,穿 越沖繩糾結的被殖民史與帝國陰霾,在霸權的支配和抵抗的鬥爭之間,批 判地觀看沖繩的影像,以及作為影像的沖繩。 幾世紀前,位於太平洋上的琉球列島尚未成為「沖繩」,而是存在著一個 封建君主制的國度——琉球王國,後經日本薩摩藩的島津氏入侵與大日本 帝國擴張,廢琉設藩遭到併吞殖民,於1879年以「沖繩縣」編入日本國家 體系之內。在二戰的尾聲、1945年激烈的沖繩島戰役後,美國的佔領統治 期長達二十七年,沖繩從此劃進冷戰年代的軍事戰略島鏈。即使至1972年 美國將沖繩「返還」日本,在「日美同盟」的交換條件下,僅為日本本土 面積千分之六的沖繩,卻佈建了整體駐日美軍逾七成的軍事設施與基地。 對某部分的沖繩來說,「戰後」彷彿被無限延長,使這個亞熱帶之島,彌 漫著由地緣政治與新帝國主義擊燃而仍未散去的煙硝。

本專題介紹國吉和夫、石川真生、比嘉豐光與石川龍一等沖繩的影像實踐 者,追索他們的生命經驗與攝影的多重構成,以及其間複雜的政治性問題 意識;同時透過評論者仲里效、岡本由希子、仲宗根香織與井上間從文的 專文,將影像之於沖繩、之於歷史,由慣常對於「如何再現」的注意力, 置放於「如何建構」的維度。從而提示了影像不僅僅是從殖民的情境中派 生,同時也反饋到殖民的情境裡,需要加以細緻地解析。 在專題的製作期間,由全球疫情激化的國際角力波濤洶湧。與沖繩同列第 一島鏈的台灣等地讀者,閱讀本專題,或許會因類似的歷史背景與政治局 勢處境而更能與沖繩共感。而在沖繩所帶來的種種啟示中,我們也將意識 到對於當下的世界正在發生的反抗——無論是以國家主義修辭掩飾的極權 主義和種族主義,或是以經濟復甦為號召的資本主義巨靈回魂,除非我們 投入更多行動與關注,否則任何國家的「強國夢」,都會是人類史上的惡 夢一場。

The “A Study of Contemporary Photography in Asia” series is a serial project that focuses on imagery culture and creative practice in various regions of Asia. Through this connection and a view that pans across Asia, we are trying to expand our understanding of the process of practice, visual experience, culture and the identifying coordinates of photography in Asia, and using such knowledge as a continuous reflection of imagery history and epistemology. Second in the series is the Okinawa issue that features Machida Megumi and Hsu Fang-Tze, both imagery researchers and curators, as our guest editors. This issue adopts a dual reading and editing process; a combination of essays and interviews brings readers through the complicated colonial history and the burden of empiricism on the island, taking a critical view of Okinawa’s imagery, and Okinawa as an imagined object while it struggled against hegemony. Several centuries ago, there existed no “Okinawa”, but the Ryukyu Kingdom, a feudal kingdom in the Ryukyu Islands in the Pacific Ocean. After the invasion by the forces of the feudal domain of Satsuma, and subsequently by the Empire of Japan, the Ryukyu Islands were annexed and colonized, and in 1879, established as the Okinawa Prefecture. At the end of the Second World War in 1945, the U.S. forces occupied and ruled Okinawa for 27 years, sealing its fate in the strategic chain of islands in the Cold War era. Even when the U.S. forces “returned” Okinawa to Japan in 1972, the island, which only constitutes 0.6% of Japan’s total land area, houses more than 70% of the U.S.s military facilities and bases stationed in the whole country under the US-Japan Security Alliance. To some parts of Okinawa, it almost feels like that the “post-war” era never ended, surrounding this subtropical island with a plume of smoke that rose from the collision between geopolitics and new imperialism. In this series, we take a look at the layered composition of the life experiences and photography by Okinawan imagery practitioners Kuniyoshi Kazuo, Ishikawa Mao, Higa Toyomitsu and Ishikawa Ryuichi, as well as the complicated political consciousness that is birthed from this interaction. We also move our focus from the question of “how to represent” to “how to construct” the background of Okinawa and its history through the essays by Nakazato Isao, Okamoto Yukiko, Nakasone Kaori and Inoue Mayumo. Through such a redirection of focus, we see the need for a careful analysis as it shows us that imagery is not only generated from colonization, but also feeds back into the issue. While putting this issue together, the world is being ravaged by the COVID-19 pandemic, intensifying power rivalries. We imagine that our readers in Taiwan and other areas, which belong in the first island chain alongside Okinawa, would feel even more relevance to the island (Okinawa), given our similar histories and political situations. As we feel inspired by Okinawa in many ways, we also become aware of the 1 struggles that are happening around the world, whether it is one against totalitarianism and racism under the mask of nationalistic rhetoric, or the return of capitalism in the name of economic recovery. Until we put into action our words and resist, any dream of a “nation of great power” is but a nightmare for the history of humankind.

※ 二手徵求後,有綁定line通知的讀者,

該二手書結帳減5元。(減5元可累加)

請在手機上開啟Line應用程式,點選搜尋欄位旁的掃描圖示

即可掃描此ORcode

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||